Cardiac Function: Blood Pressure vs. Flow: Why such confusion?

In articles about cardiac function, there are errors due to a lack of understanding of the basic principles of how pumps work. I believe there is a mis-application of the pressure-flow-resistance equations.

Is Flow proportional to Pressure?

Equation #1: Q = kPr / r (where Q=volumetric flow rate, Pr=pressure change, r=resistance, k=some constant)

From this equation we see that flow is proportional to pressure. It means that in a given section of pipe with given resistance r, if we increase the pressure difference across it, the flow will increase. Makes sense right?

But, HOW is pressure created? Does the heart (or any pump) by itself "create" a certain pressure? To attempt to answer this question, let's imagine a scenario: We know that the blood pressure during Systole (the "pump") reaches about 120 (mm Hg) in a healthy human. [side note: if the systolic pressure in your arm is measured to be 120, it's probably a bit higher in the aorta because it is upstream.] Let's say that (horror of horrors) we completely cut open the aorta to the atmosphere just before the next LV (left ventricle) contraction.. so that the entire cross section of the aorta is now open to (relatively low) atmospheric pressure. What will be the measured blood pressure just inside the aortic opening when the heart does its contraction? It will peak at FAR LESS than 120. And if we measured the flow rate coming out, the flow would be GREATER than the previous contraction. This seems to be in opposite to the above equation, but is it? That's right, we'll have lower pressure and higher flow at the same time... but the equation holds true because the resistance was drastically cut to almost zero (pun intended).

But did you miss this part? The heart does not generate any specific pressure by itself! Cutting open the aorta drastically reduced the measured pressure. So, calling the heart a "pressure generator" is a bit of a misunderstanding.

Also, let's examine from another angle the above equation #1. According to the equation: if we reduce the resistance to zero, the flow rate would be infinitely large! But that won't happen because the pressure dropped. In the case of the cut-open aorta, the flow rate would be related to the speed that the heart contracts.. and no faster. The LV will not contract with infinite speed. So, we see that there are limits to the application of that equation, but it holds true within realistic ranges of the three variables. In this example, the heart seems to be more of a "flow generator" with flow rate determined by the LV contraction speed and volume.

So how do we get out of this mess? Pressure generator vs. Flow generator? It's not a cop-out to say there is no winner! The simplest way, is to see that a pump doesn't really care what you call it, it just moves its parts (in general layman's terms), just like your hand squeezes its fingers against both a handful of feathers and a tennis ball, and naturally behaves differently with each. The difference is primarily made by the resistance. If blood vessels and capillaries dilate, that's a reduction of (r) in the equation. But as a consequence, (P) will reduce and (Q) will increase, because the heart does not generate a specific constant pressure... it just moves its parts against a flow resistance. This applies to the heart just as it does with simple man-made pumps.

Thus, the resistance of the circuit is a primary thing to study.

Now, here is another equation, depicted by the following graph: (from Is the heart a pressure or flow generator? Possible implications and suggestions for cardiovascular pedagogy | Advances in Physiology Education | American Physiological Society)

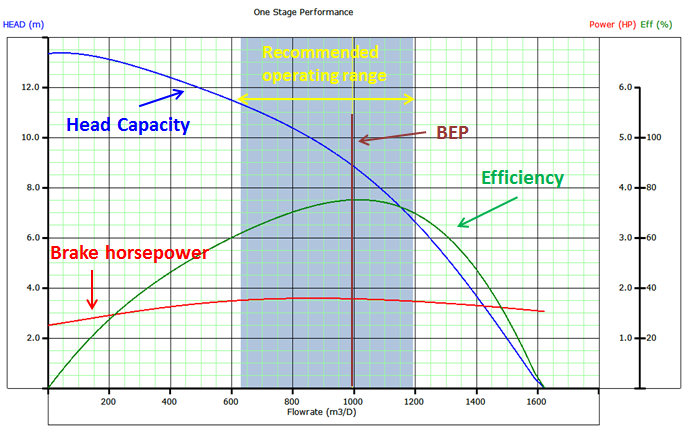

And another, from an example man-made mechanical pump: See the blue line, the Pressure (head) vs. Flow curve:

( graph #2, credit to https://production-technology.org/ )

These curves explain how the flow rate increases when pressure drops. How can this possibly square with the first equation #1 above? Because the missing variable here is, you guessed it, the resistance. The above graph isn't showing pressure vs flow at a constant resistance, it's showing pressure vs flow as the resistance varies. In other words, as resistance decreases, the point of operation moves from upper-left to lower-right along the blue line. Thus, if resistance decreases, then as a result pressure drops and flow increases... but why do both pressure and flow change simultaneously? Wouldn't the equation #1 be satisfied if only one of those variables changed? The equations to explain the answer are advanced, but it just happens naturally. The graph #2 is showing the actual observed behavior when the resistance changes, for that particular pump. A simple pump (or the heart) does not have a fancy mechanism to tightly control either the pressure or the flow (because they don't need to), as we saw above in the "open aorta" scenario, and as we see in the chart #2 above.

What's missing in equation #1 that might help understanding is the pump's power output (energy expended over time), typically expressed in Watts or Horsepower. That is something critical that is missing in understanding cardiac function, because obviously the heart can only pump with a maximum amount of power before failing.

Equation #2: Power = cQ x Pr Which is (mass flow rate x pressure change x some constant c)

Eq 2 explains WHY the blue curve above has the shape it does. For a given power setting, Q and Pr are inversely proportional.

Notice in this graph, the mechanical pump horsepower (red line) is fairly constant within the recommended range of operation (shaded area). As with the heart, within a limited range of power output, the heart moves the blood around with significant flow variation DUE TO THE CHANGES IN RESISTANCE of the vasculature (reference). During exercise, there certainly is an increase in power usage/output, we know from research showing an increase in pressure as well as flow rate, but with a reduction of resistance as well (reference). It's well known that hard pipes (stents, etc) cause problems for the heart during exercise, and patients need to be cautious (reference). In other words, the reduction in resistance due to dilation is essential to avoid overtaxing the heart and nearby arteries.

[To be continued...]

Comments

Post a Comment